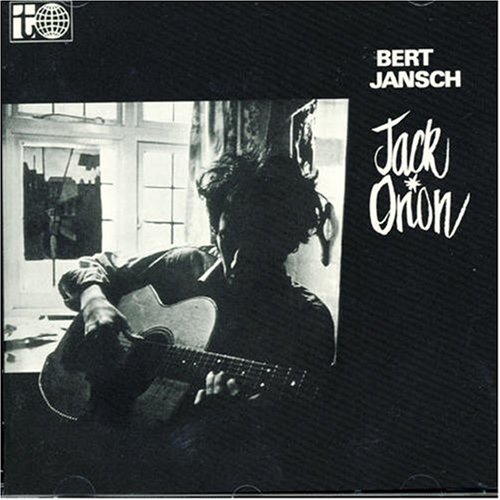

Having recovered sufficiently from cancer to be able to tour USA with Neil Young last year, Bert Jansch is now seriously ill again.We, who have loved his music over the years since his eponymous album hit our turntables back in 1965, but for me the really seminal moment was his still stupendous Jack Orion album the following year.

That was in the days when "folk rock" meant record producers adding electric backing to Paul Simon songs; Fairport's Liege and Lief was no more than a gleam in Dave Swarbrick's ear. I was advising Sandy Denny she'd be better singing jazz.

And his version of Blackwaterside nearly landed me in court.

It happened like this:

In 1969 I received a surprising call from Nathan Joseph, boss of Bert's record company, Transatlantic. He wanted to know if I was willing to appear as an “expert witness” in a legal action he was planning to take against Peter Grant, the notoriously thuggish manager of the Led Zeppelin rock group, for breach of copyright.

He maintained that Black Mountainside, an acoustic guitar feature from Jimmy Page on Zeppelin’s first album, was a note-for-note copy of Black Waterside, recorded by Bert Jansch, on his third album, Jack Orion. I’d reviewed the album enthusiastically for Melody Maker, applauding its blend of contemporary guitar accompaniments and traditional lyric:

“At first sight the idea is horrifying, a bluesy guitarist who has hitherto concentrated upon contemporary subjects singing the big old ballads of the true traditionalist. In fact, Jansch’s interpretations illuminate the songs from a completely new angle. As sung by him, the brutal world that created the old ballads doesn’t seem so very far off from the world of The Needle of Death.”

(The latter being the title of Jansch’s lugubrious commentary on the perils of heroin addiction, inspired by the death of a friend.)

But I had also written at length on the objectionable practice of attempting to copyright folk songs, which Black Waterside was, undoubtedly. In my view, they should all be considered in the public domain. The entire area of folksong copyright was a veritable can of worms. There had been notorious instances of this, few of which had actually come into the courts with any measure of success: the way Chas McDevitt had turned Freight Train, which he had learned from Peggy Seeger, who had heard it from her nurse, Libba Cotten, when a child, into a monster hit, retaining all the royalties without a penny going to either Ms Seeger or Ms Cotten (or not until M’Learned Friends became involved); the way Paul Simon had borrowed Martin Carthy’s ostinato guitar riff for Scarborough Fair, and turned it into another money-maker, especially when Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme (as he called it) was used on the soundtrack of Mike Nichols’ 1967 movie, The Graduate; the way, when Ewan MacColl refused to copyright his mother’s version of Lord Randall when he recorded it, it was then recorded by the Spinners folk group, who finding it unprotected, promptly copyrighted it themselves, so not only did they get the royalties from their own version, but also grabbed any monies from Ewan’s own recording of his mother’s song.

I had tried to persuade Norman Buchan, MP, when he was responsible for cultural matters in the Labour Government, to investigate the possibility of new legislation which would pay all royalties from traditional music into a central fund, to be shared between the efforts of folksong collectors – mostly engaged in a thankless and often far from cost-effective labour of love – and their informants. Buchan had been a pioneer of the Scottish folk revival when he was a humble teacher at the Rutherglen Academy, and he knew more about folk music than most politicians.

As it stood, copyright was a creation of the age of print, and it took no cognisance of oral folk culture. So if a singer sang a song that had been in the family for generations to a collector who wrote it down, then the act of scribbling it into a notebook created the copyright – not for the informant, but for the collector. If, using more modern technology than the notebook which had been Cecil Sharp’s preferred method, the collector used a sound recorder, then the copyright in that recording but not in the song would belong to that collector, not the singer nor the singer’s family. If someone else played the recording, and transcribed it on to paper, then that act conferred copyright on that third party, clearly a nonsense.

Sharp himself gave his view in 1907:

“The law protects the product of the man's brain, not the thing on which he exercises his wits. . . . A collector who takes down a song from a folk-singer has an exclusive right to his copy of that song . . . It is always open to someone else to go . . . to the same source, exercise the same skill and so obtain a right to his copy.”

Buchan organised some meetings at the House of Commons to work out a procedure that would be acceptable to all interested parties, but it foundered upon the opposition of Novello & Co, the music publishers (now part of EMI Music and, incidentally, publishers of my own songwriting efforts), who were unwilling to part with their own copyrights, which had been attached to the over four thousand songs Cecil Sharp had collected in England and America. Then Buchan died, a sad loss to music and left-wing politics, and the efforts to introduce some rationality into the business petered out.

So who owned Black Waterside? The version sung by Bert Jansch and, before him, by Annie Briggs, had been taught her by Albert Lancaster Lloyd, genial eminence rouge behind the folk revival in Britain. Lloyd had presumably learnt it from the recordings Peter Kennedy and Sean O’Boyle had made of Paddy and Mary Doran, two Irish tinkers, in 1952 (the man and his wife sang completely different melodies to essentially the same set of words). But Kennedy was an employee of the English Folk Dance & Song Society at that time, on secondment to the BBC. Did the recordings he made belong to him, the BBC, or the EFDSS? No doubt all three would maintain their rights. In the recordings, that is, not of the song’s text and melody. Kennedy published words and music of a version he and O’Boyle recorded from Winnie Ryan of Belfast, in his Folksongs of Britain & Ireland (Cassell, 1975), the title page of which carries the legend: “Text © copyright Peter Kennedy, 1975, Music © copyright Folktracks and Soundpost Publications.” But since it says, also, “Musical transcriptions and guitar chords by Raymond Parry”, then surely the music is Mr Parry’s copyright.

Also, the BBC recorded the Dorans at the Puck Fair in Killorglin, Co. Kerry, five years earlier. So perhaps that earlier recording established the BBC’s rights, prior to Peter Kennedy’s.

Cecil Sharp noted a version from a Mrs Overd in Hambridge, Somerset, in 1904. Versions were printed by Frank Kidson in 1891 and 1927, and others have appeared in print dating back to 1787. Sharp collected three versions in Virginia and North Carolina, USA, in 1917, and the song has also appeared in Baltimore and Canada.

The idea that collectors make fortunes out of their work dies hard. Sharp recorded an exchange as he noted down a song from a woman engaged in her weekly wash: “In one of the intervals between the songs one of the women remarked, ‘You be going to make a deal o’ money out o’ this, sir?’ My embarrassment was relieved by the singer at the wash-tub, who came to my assistance and said ‘Oh! it’s only ’is ’obby.’ ‘Ah! well,’ commented the first speaker, ‘we do all ’ave our vailin’s.’”

George “Pop” Maynard, who besides being a superb traditional singer was also marbles champion of the world until his dying day, once asked me the same question about Peter Kennedy. He looked sceptical when I assured him there was no money to be made from collecting. I might have added that money might be made by ripping off the work of collectors and copyrighting it in your own name.

All this neglects the essential point about folk music, that, rather like a jazz soloist, each “performance” (if one may apply such a description to a situation where singer and audience are a community sharing an experience as foreign to the concert stage as a producer co-operative is to a capitalist megacorp) is unique.

Sharp observed of Henry Larcombe, a blind singer from Haselebury-Plucknett, from whom he got an 11-verse version of Robin Hood and the Tanner, which was identical to a black-letter broadside in the Bodleian Library and therefore he argued must have been “preserved solely by oral tradition for upwards of two hundred years” that

“He will habitually vary every phrase of his tune in the course of a ballad. I remember that in the first song that he sang to me he varied the first phrase of the second verse. I asked him to repeat the verse that I might note the variation. He at once gave me a third form of the same phrase. I soon learned that it was best not to interrupt him, but to keep him singing the same song over and over again, in some cases for nearly an hour at a time-the patience of these old singers is inexhaustible.”

Of Mrs Overd (from whom, it will be remembered, Sharp got a version of Black Waterside), Sharp noted that in one song, “the final phrase appeared in four different forms. These variations were not, however, attached to particular verses, though Mrs Overd never sang the ballad to me without introducing all four of them.”

One may pin down one such performance on to the printed page (which Percy Grainger tried to do, often to ludicrous effect), but even if the variations in melody and tempo between different verses are transcribed as faithfully as print will allow, they are as removed from their origins as a butterfly in a museum cabinet is from the real, fluttering beauty of the living organism.

As Margaret Laidlaw, James Hogg’s mother, told Sir Walter Scott when he printed some of her family ballads:

“There was never ane o’ my sangs prented till ye prentit them yoursel’ and ye hae spoilt them awthegither. They were made for singing an’ no for reading, but ye hae broken the charm now, and they’ll never be sung mair.” (James Hogg, Domestic Manners of Sir Walter Scott, 1834)

Grainger pioneered the use of a phonograph recording machine precisely to allow more accurately to notate the variations between verses, but this still froze a single performance, like a fly caught in aspic, with no appreciation of the wide variations possible from the same singer. Grainger’s manuscript notes of Joseph Taylor’s Creeping Jane, with its tempo swinging between 4:4 and 12:8 time signatures, is markedly different from the way Taylor sang the same song for the HMV gramophone company in 1908.

We are dealing here with an oral culture rather than a literary one, and this was as true of Bert Jansch’s unique accompaniment to Black Waterside as of the words and music. According to journalist Colin Harper, Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page had learned the tune from Al Stewart, who had assumed (wrongly, as it turned out), that Jansch had used the same DADGAD tuning pioneered by Davey Graham for his recording of She Moves Through the Fair, a composed song from the pen of Padraic Colum, which the entire folk world had learned from the singing of Margaret Barry, a banjo-playing Irish tinker street musician who made her home in London’s Camden Town during the Fifties. Maggie had learned it from a 78rpm shellac recording by “Count” John McCormack. So much for the “folk process”.

Back to Bert Jansch and Black Waterside. His tuning was actually DADGBE, ie normal guitar tuning with the bottom E dropped to D. So however like his version Jimmy Page sounded to the untutored ear of the audiences for both, it was actually quite different.

This was the situation confronted by John Mummery, QC, an eminent barrister specialising in copyright, when he was briefed by Transatlantic’s Nathan Joseph. Colin Harper quotes Joseph:

“What Mr Mummery advised was that whereas there was a distinct possibility that Bert might win an action against Page, there was also the possibility that all sorts of other people might then say, ‘Ah, but Bert heard it from me.’ Given the enormous costs involved in pursuing an action, and the thought that one could be litigating, or being litigated against, for the next twenty years on the basis that everybody and his dog would claim Blackwater Side or Mountain Side or any other kind of side, we left it at that. As the ‘writer’, Bert would have had to share the costs with us fifty/fifty - and they were not the sort of costs that we could afford, let alone Bert. But in many ways it was a very interesting case. If you think about it, almost any “traditional” song that somebody does an arrangement of, somebody will have done something vaguely similar before. The difficulty appears to be one of really establishing, amongst hundreds of arrangers, who it was that made the arrangement ‘original’.” Colin Harper: Dazzling Stranger – Bert Jansch and the British Folk and Blues Revival (Bloomsbury, London, 2000, p. 5)

And so I was not called as an expert witness after all. But the bizarre sequence of circumstances that led from an Irish tinker’s camp in 1952 to a possible legal precedent of great significance in what had now become a multi-million-dollar popular music industry, in which the songs of unlettered folk become the subject of high-powered legal briefs, is a story that begins, not in 1952, but half a century earlier, when the Royal Family’s music teacher saw something remarkable when peering out of a vicarage window.

That's a story I'm working on right now, but meanwhile all those of us who pray should be praying for Bert now, for another recovery from this destructive illness.

Meanwhile, whether you pray or not, you can post messages of appreciation here and I will pass them appropriately.

Get well soon Bert. We need you today, more than ever.